Encountering John Updike as book reviewer is to witness something akin to the 8th wonder of the world. I calculate that the time it takes for him to write as much as he d oes (speaking here of volume) leaves no time for reading, much less reviewing, books written by other people. My calculations have to be pretty far off the mark. He reviews like a fiend. (I mean this in the most positive sense of the term.) And reviewing is but one of the many grooves his writing follows. Is there any form he does not indulge?

oes (speaking here of volume) leaves no time for reading, much less reviewing, books written by other people. My calculations have to be pretty far off the mark. He reviews like a fiend. (I mean this in the most positive sense of the term.) And reviewing is but one of the many grooves his writing follows. Is there any form he does not indulge?

I might not be so impressed by the monumental volume of his output if it were not for the other, more fundamental impression Updike makes. He is a master writer. People who write better than I, and not nearly as well as Updike (by their own confession), have been saying this about him for decades. With Updike, you need not begin with an interest in any topic he takes up to be delighted with his perspective.

For example, in an essay titled “Groaning Shelves,” he reviews the book The Book on the Bookshelf, by Henry Petroski. A book with a title like that would tempt me. In the scope of five pages—seven paragraphs—by Updike, I experience at least as much pleasure and add every bit as much to my fund of knowledge as I would expect from reading Petroski himself (279 pages). Come to think of it, the relish of reading Petroski firsthand is converted to relish in not having to read it because of the relish of reading Updike on Petroski.

In the first paragraph, Updike describes the publishing niche of this professor of civil engineering and history, mentions two of his previous books, The Pencil (1990) and The Evolution of Useful Things (1992), identifies the primary sources for Petroski’s third work, here under review, and demonstrates that The Book on the Bookshelf (1999) would not have been much of a book without the use of stretching devices, since the territory (“the history of book housing”) has been pretty thoroughly scampered over by others before Petroski.

What we learn from Updike in this first paragraph is technique in the art of book reviewing that requires having something to say about a book that says little more on its topic than what others have already said in earlier books. We also learn something about Updike—that this is no reason to leave the book alone or end a review having said as much. Something else about Updike: he judges that arranging the books in one’s personal library in accord with the Dewey decimal system is “whimsical” rather than “obvious.” (It seemed obvious to me several years ago when I adopted the system. Ironically, perhaps, this gentle chastening by Updike, for being whimsical when I thought I was being practical, was reinforced the day before reading his review; I learned with mixed emotion that the latest version of bibliographical software I use—namely, Bookends—enters the Library of Congress call number in the designated field for each new book reference. I’m now in engaged in a tedious cost-benefits analysis of switching over to the LC system from this point forward.)

What we learn from Updike in this first paragraph is technique in the art of book reviewing that requires having something to say about a book that says little more on its topic than what others have already said in earlier books. We also learn something about Updike—that this is no reason to leave the book alone or end a review having said as much. Something else about Updike: he judges that arranging the books in one’s personal library in accord with the Dewey decimal system is “whimsical” rather than “obvious.” (It seemed obvious to me several years ago when I adopted the system. Ironically, perhaps, this gentle chastening by Updike, for being whimsical when I thought I was being practical, was reinforced the day before reading his review; I learned with mixed emotion that the latest version of bibliographical software I use—namely, Bookends—enters the Library of Congress call number in the designated field for each new book reference. I’m now in engaged in a tedious cost-benefits analysis of switching over to the LC system from this point forward.)

The second paragraph begins with a sentence that must have been a relief to Petroski: “Nevertheless, we need to be reminded that people did not always live surrounded by books arranged on shelves, with their spines outward and stamped with the title, author, and publisher.” On this point, I take issue with Updike. I’m not sure we “need” to be reminded of such things, or even that we ever “needed” to learn such things. This may be Updike’s way of persuading himself that Petroski’s book is worthy of review. He surely needs to convince his readers, given the mediocre assessment implied in Updike’s first paragraph.

The balance of paragraph two re-traces the earliest stage of “book” production (papyrus rolls) and the practical solutions that were devised for the problem of their convenient storage. One sentence, albeit parenthetical, glistens: “In truth, only in certain circles, smaller than academics like Petroski might imagine, could people be said [even today] to be surrounded [by books]; I am frequently struck by how many otherwise handsomely accoutered middle-class American homes have not a book in sight.” I know that experience—the experience of not only seeing this to be the case, but also the experience of being “struck” by the fact. I am, of course, an academic. (Not that being struck by the absence of books in the homes of other people is a sufficient condition for being an academic, except in that “special” sense of being eccentric.)

The next four paragraphs carry on the exposition, in chronological sequence, of book production and storage adjustments, leading up to the present, when the volume of books at institutional libraries, it is estimated, doubles about every sixteen years. Updike boils down, in five paragraphs, the history of this transmigration of the souls of books. Even to the layman, it is an interesting history, if told well and in no more than five paragraphs.

I knew nothing before of “chained libraries.” I’m not sure I quite have an adequate picture in mind of this invention that served for several centuries. The most interesting fact I learned is that “even after books came to rest on shelves, their spines were unlabelled and faced inward.” Updike surmises that “when books were few, they did not need to be labelled, any more than do familiar people.” I’m not about to experiment with this technique of book arranging with my several thousand volumes (although the storage of many hundreds in boxes is hardly more satisfactory).

The eighteenth-century member of Parliament, Samuel Pepys (pronounced “Peeps”), most famous for his Diary, was apparently compelled (by his wife?) to constant winnowing of his own book collection, so that it never exceeded the manageable limit of 3000 volumes. He ensured efficient use of space for his books by arranging them in two rows, tall books in front, shorter books behind on raised shelves, a strategy that is “impressively harmonious, though somewhat forbidding to a would-be browser.” You can see this for yourself at Magdalen College in Cambridge, where twelve cases of the Pepys collection are preserved.

The eighteenth-century member of Parliament, Samuel Pepys (pronounced “Peeps”), most famous for his Diary, was apparently compelled (by his wife?) to constant winnowing of his own book collection, so that it never exceeded the manageable limit of 3000 volumes. He ensured efficient use of space for his books by arranging them in two rows, tall books in front, shorter books behind on raised shelves, a strategy that is “impressively harmonious, though somewhat forbidding to a would-be browser.” You can see this for yourself at Magdalen College in Cambridge, where twelve cases of the Pepys collection are preserved.

As always, after reading Updike, my vocabulary is much improved. I now know how to identify the “fore edges” (not “four edges”) of a book. I’ve got a sprinkling of new Latin terms under my belt, which should come in handy next time I cross paths with Seneca: volumina, capsae, armarium commune. Speaking of Seneca, he opined that those who ostentatiously surround themselves with books as mere ornamentations of their digs make themselves ridiculous, or something to that effect.

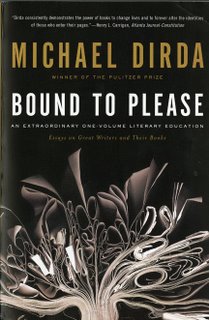

“Groaning Shelves” appears in a 700-page collection of John Updike’s writings over a period of eight years, third in a series of such collections. This volume is called Due Considerations: Essays and Criticism (2007). It contains nearly 150 brief essays. Since yesterday, I’ve read eight of them, including: “On Literary Biography”; “A Case for Books”; “Looking Back to Now” (not unlike Jorge Luis Borges); “Against Angelolatry”; a tribute to Eudora Welty; Updike’s Introduction to Seven Men, by Max Beerbohm; “Groaning Shelves”; and one other whose title I’ll withhold, lest you infer something disagreeable and false about my (or Updike’s) character.

I purchased my copy yesterday, after browsing the entry on “The Future of Faith” (pp. 27-41). I excluded this from my count in the previous paragraph because I haven’t yet read it closely. But I know that I will, and soon.

Amazon Paperback

You can now find Alvin Plantinga’s book Warranted Christian Belief (Oxford University Press, 2000) at Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Click here. It can be read online or downloaded in plain text for free. For the modest fee of $2.95 you can download it in PDF format.

You can now find Alvin Plantinga’s book Warranted Christian Belief (Oxford University Press, 2000) at Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Click here. It can be read online or downloaded in plain text for free. For the modest fee of $2.95 you can download it in PDF format.

To improve your enjoyment of Jerome K. Jerome (1859-1927) and to find more to appreciate about the talents of Hugh Laurie (b. 1959), you can do both at once. Just go to

To improve your enjoyment of Jerome K. Jerome (1859-1927) and to find more to appreciate about the talents of Hugh Laurie (b. 1959), you can do both at once. Just go to

Recent Comments